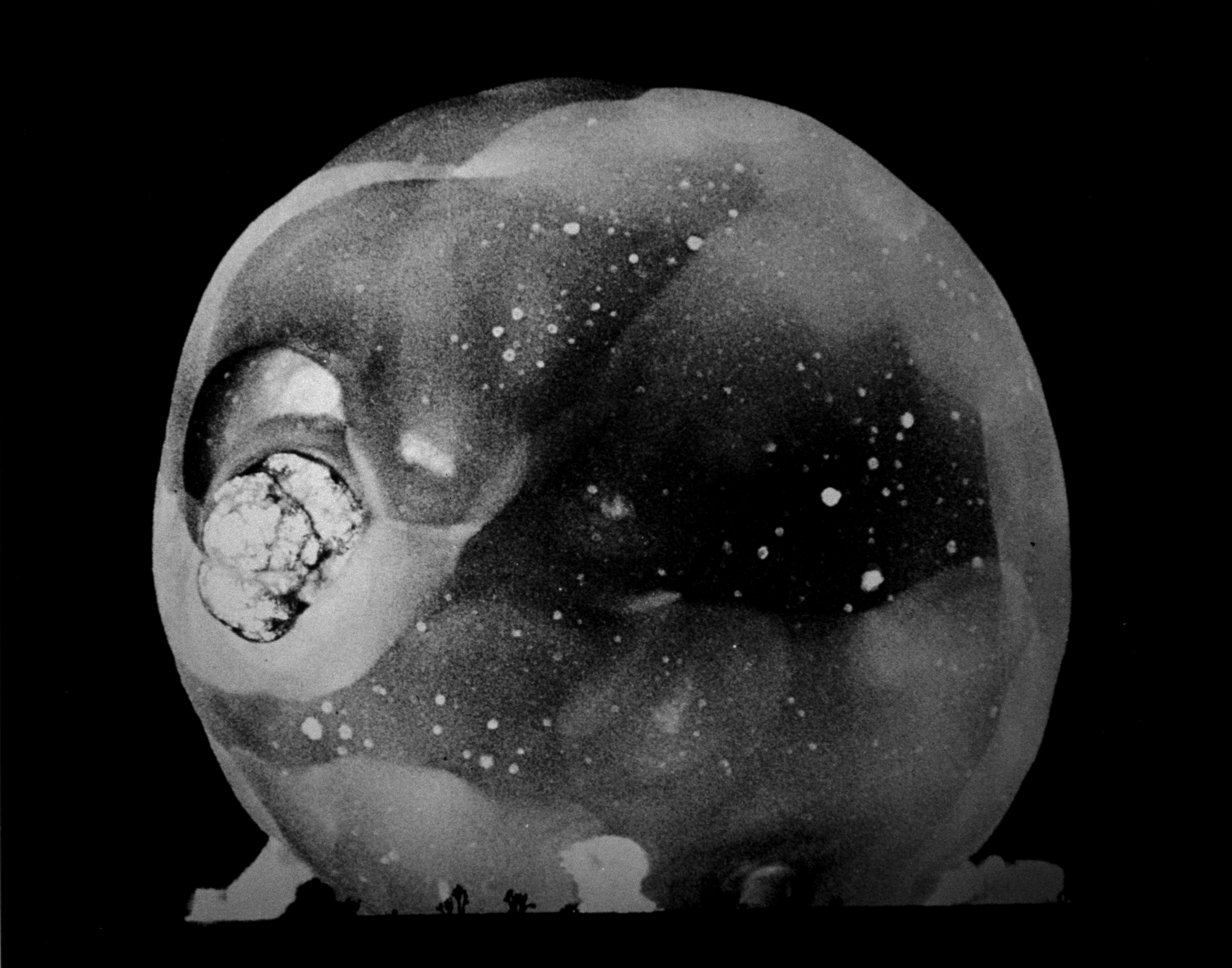

Harold Eugene Edgerton. Atomic bomb explosion. Ca. 1952. (Source: MIT Museum Collection, https://mitmuseum.mit.edu/collections/object/HEE-NC-52011)

This is not the eponymous "Question 7" of Richard Flanagan's novel, but it is a question in the book, one that has caught my attention. "Question 7" is, in both its structure and themes, a strange book. It tries to talk about many things: life and death, the author's father, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, the fiction and love life of H. G. Wells, the genocide of the Tasmanian natives, the unbearable weight of the past in all that is present and how it feels to drown in a river. But Flanagan makes it work. I won't spoil the book, because there is nothing to spoil here; there are only things to experience.

What picqued my curiosity was Flanagan's unusual conception of history. As presented in the novel, history is not just a linear series of events, all arranged in order across time, one after another. History is rather like an echo in a cave or a ripple in a pond, always coming back to us, leaving traces in the future. Flanagan was trying to write this book in order to come to terms with a particular event: him almost drowning in a river while riding a kayak. For you to read his book, he had to write it; for him to write it, he had to be born and grow up in Tasmania, where his father came back after World War II from a Japanese labour camp, which he survived because Japan surrendered after Thomas Ferebee dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, a bomb which had only been built because a Hungarian expatriate scientist worried that Hitler might unleash the power of the atom first, and he only had that worry because he had read about it in a mediocre story by H.G. Wells, who himself wrote it while abroad, thinking about his mistress and trying to reclaim the success of his first works.

So where does it begin? What came before H.G. Wells? Can we ever draw a line somewhere, in the sand of time, and separate the past from the present from the future? For Flanagan, this is impossible. History is not a straight line and the past is never over, meaning that it always bears consequences on the present and the future. As Flanagan reminds us, "life is always happening and has happened and will happen." For you to read his book, millions of Tasmanian natives and Japanese civilians and World War II soldiers had to die (and are dying and will die), without finality. "Question 7" is a book that refuses to be just that, just a book or, worse, a "historical novel", because it acknowledges that all that came before us is what makes us who we are and we cannot run away from it in the present (although many attempt to do so.) Reading this book is equivalent to the fission of a literary atom: it unleashes an emotional energy that the reader never knew possessed - and in the process, it obliterates any conception that we might not be here together.

And so, after reading "Question 7", I couldn't just go back to my day-to-day life and pretend like it was just another book, another cultural product to be consumed and put back on the shelf. My question was (and still is): "How can anyone bear this immense weight of the past?"

The Angel of History

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, 1920

Walter Benjamin was a Jewish literary critic who ran away from Germany in the 1930s, when the Nazis came to power. He ran to Nazi-occupied France and attempted to flee to Spain, but with no success, and so he chose suicide. He left behind, among other things, a set of writings called On the concept of history, more widely known as Theses on the philosophy of history. There is one passage in there, from Thesis IX, that has been quoted extensively in critical theory, and I am no different in this regard. It is the one concerning the "angel of history":

A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.Walter Benjamin, On the concept of history, p. 152

The passage is extremely evocative, but what does it mean? Well, Benjamin is forcing us to re-evaluate how we see history. He offers us this image of an angel that is propelled across time, not knowing where he is heading because his face is always turned to the past. And no matter how much the angel struggles, he cannot stop the 'storm' that rushes him forward. So far, the angel's vantage point is the same as ours: we, too, are forced to look back on what has already happened, unable to stop the march of time. But here is the difference: the angel, unlike us, does not see a mere "chain of events", but "one single catastrophe" that keeps accumulating. In other words, for the angel, the past is never the past and the victims are never just so many years or centuries or wars removed from us. They are always here, in our vision, but we choose (or are forced to) look away from them. The mist of history and how we construct it obliterates the view and renders it unrecognizable. I, myself, for example, had never learnt anything about the Tasmanian genocide before reading Flanagan's book.

This is the Tragedy, with capital T, of history, the Tragedy that keeps on happening and will keep on happening, while the wreckage keeps piling up. People have died throughout history as victims of cruelty and injustice, and we cannot do anything to change that. How do we react to this? How can we react?

"How can one bear this?"

Alice Oswald's poem, "Memorial" (about which I learnt from Jacob Geller's video on it) is a sort of retelling of Homer's "Iliad." However, instead of retracing the epic's plot, it offers us a list of names of the warrios who had fallen in battle, describing, for each of them, the circumstances of his death. It is a poem with an equal voice, a poem that asserts that death has happened, but does not offer space for mourning. How could it, when the list runs on and on for about 200 names? Even if we tried to mourn the fallen warriors, we cannot. For once, there are simply too many of them. The human heart cannot take in the emotion of so much loss without it eventually becoming tiring. And even if we could, what do we know of them? What do we say? They are not the main "cast of characters" of the epic. They were just people who died, a long, long time ago.

What if, instead of fallen Greek warriors, they were people killed in Gaza? It's been almost two years of bombing now, and Israel has recently announced their plans to completely seize the land of Palestine. Meanwhile, Western nations have been busy pencil-pushing (when not selling weapons to Israel) and arresting protesters. And people die. How do we reckon with that?

I wouldn't have written this post about two years ago (in fact, I couldn't, since the dots connected only after reading Flanagan's book,) because then I would have been at fault: to treat the people of Palestine as victims of a genocide when it was just starting was to treat them as being already dead, which can just as well lead to dehumanization, making their deaths a foregone conclusion. This is perhaps the most horrible irony of history: you cannot convince people to stop a genocide because there is no proof that it is happening, and when the proof comes forth and the extent of the massacre is revealed, people have already died (and are dying and will die). The protesters have asked and keep asking, "How can you not care about this?", but I think the real question is: how can one care when confronted with this?

A key concept in understanding "Memorial" is the Greek word enargeia meaning 'vividness', but also translated as "bright, unbearable reality." It refers to an event or a feeling like a spotlight: powerful, blinding us, fixing us in place, overwhelming us. And genocide is an event of enargeia, a bright, unbearable reality, so powerful and overwhelming that one cannot help but turn their eyes away from it. Violence on such a scale can never be fully related to another, documented or understood, just like the horrors of a Japanese war camp could not be related by Flanagan's father to his son.

In order to disentangle his father's past, Flanagan travels to Japan, while saying that he is collecting historical information for a new book. But he does not find anything there, no revelation. The mine where his father worked in, along other prisoners, is closed and it has a small museum. A smiling Japanese lady tells him about the history of the mine, giving him a tour that is as basic as one would expect. There is no mention of the prisoners working in the mine, of their beatings or of their dead. Later, Flanagan meets with an old warden from the camp, who welcomes him into his home. The warden talks to him about his time with the prisoners, giving only vague details about what was happening there, but also recounting the punishments applied. When he learns that Flanagan's father had been a prisoner, he gives him yen worth 20 dollars, which Flanagan promptly throws into the trash after leaving the apartment. Is this "the banality of evil", as Hannah Arendt called it, or is it just the wreckage of history growing ever taller? We feel justified when we feel something stirring in our hearts and demanding justice for the prisoners in the Japanese war camps, for the civilians dying in Gaza, for the soldiers in Ukraine, for the people incarcerated and deported by the Trump administration. But I have to ask an uncomfortable question: what would that justice even look like?

Justice and history

Justice is usually conceived as a proportional response or punishment to a crime. Approaches to it can be divided in two: retributive or rehabilitative. Retributive justice seeks to undo a crime by punishing the wrong-doer and/or restoring what was set wrong by the crime. Meanwhile, rehabilitative justice seeks not to punish a criminal for the sake of punishment, but to make sure he does not commit such crimes again. How, then, can these concepts be applied to a 'catastrophe' the size of a genocide?

Retributive justice would not work. Even if we took out the leaders responsible for a genocide, what do we do with those who carried out their orders of extermination? Or the people who could have done something, but chose not to? We are all guilty, in this sense, and there is no power in this world great enough to punish such an immense number of people. Furthermore, retribution cannot be achieved, because the dead cannot be brought back to life and a genocide cannot be carried in reverse, against the oppressors. Likewise, rehabilitation is unlikely, once again because of the number of people it would have to be applied to, but also because the sheer enormity of the crime makes the reaction feel unbalanced. "You have committed a genocide. Now you will spend time thinking hard about what you did and learning that genocide is wrong." It is a frivolous view, that ignores reality.

What do we do, then? We have two other options available. One is to wait for a Messianic event, a single point in time, like the Second Coming of Christ, where a superior power would insert itself into history and right all the wrongs. I cannot say if such a power exists or not, but it is a terrible gamble: if we are wrong and the Messianic moment never arrives, then weare just letting atrocities perpetuate. Another option is to discard morality, in a sense. If history is full of untold destruction and injustice, then the best we can do for ourselves is to try and run away from it, not caring who else might be affected. Besides the fact that running away is not always possible, it also leaves us once again with nothing to do against injustice and suffering. And if we try to create our own temporal justice, then, as we have seen above, it is unlikely to be applicable or meaningful. Perhaps, then, justice is not a category of history. In other words, we try to see the relations in the world in terms of just and unjust, which may work in the usual, small-scale settings in our lives, but it cannot extend to historical atrocities or apply meaningfully to them.

Or as Flanagan put it, "Tragedy exerts its hold upon our imaginations because it reminds us that justice is an illusion."

A quasar

How can one live if there can never be justice done for those who suffered and died? How can one live knowing that no atrocity, no matter how hard we try, can ever be undone, not by humans, anyways? These questions, to be honest, obsessed me, and, just like with Question 7, it would be foolish to try to answer them. They can only ever be asked and considered, but not truly answered.

Still, I don't want to leave you, the reader, in a state of despondency. So I've tried to sketch not an answer, but a way of making the answer possible.

This may sound silly, but bear with me, please. Consider a quasar in the depths of space, pulsing and eternally shooting off the same signal, repeated. The quasar is alone and its message travels in vain, perhaps unable to ever be received. Even if it reached us, that would be millions of years later, and what we would receive would be something that does not exist anymore, but which still travels to us, to the present, like a ghost. The same way history travels and encroaches upon the present, holding it ever in its sway.

Thomas Ferebee, the man who dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, was the same man who had earlier dropped bombs on Rouen, in Nazi-occupied France. Fifty-two people were murdered and 120, injured. But Flanagan also tells us in his novel about a man who lost everything in the bombing.

One Frenchman returned to his home to find it destroyed. At the morgue he discovered among many others the corpses of his parents and his son, naked, still bleeding, with only their socks left on their bodies. Of his daughter no trace was ever found.Richard Flanagan, Question 7, p. 233

He then proceeds to ask us who remembers the dead, other than those who were close to them? Who remembers the dead of the Vietnam War? Who remembers the dead of the natives of Tasmania? And who remembers a single vanished daughter among so many other dead in World War II? Well, her father does. And perhaps we should, too.

If justice cannot apply to history because history contains too much enargeia, too many bright, unbearable realities, and if we, like Benjamin's angel of history, can only see the past and its untold destruction, then the least we can do is to not look away. The least we can do to bear the accumulated weight of injustice and suffering is to accept the blinding spotlight that shines into our face until it goes out or we go blind, to not give up on it, to not forget what happened and continues to happen, as long as we exist.

To try to answer the question, we must look for those who vanished, like the Frenchman lookeing for his daughter. Only, their trace is not somwehere specific, in some other world, but, as I have repeated, here, with us, in the present, like the signal emitted by a quasar that no longer exists. The trick, I believe, is to remember one neither as a mere individual, a name like those in Oswald's "Memorial", nor as an all-encompassing icon that could stand in, without issue, for any of the countless others who have died. Instead, I think the dead should be remembered as stars (or quasars, if you please), emanations that extend from their time to ours, that reach out, even if it is incredibly difficult to see them, but which shed light on both our present and our future.

(P.S. Richard Flanagan's "Question 7" has won the Baillie Gifford prize for nonfiction in 2024. I don't know why that was the category chosen for it. The past is never anything but a compelling fiction, although it is very often a fiction that bites.)

References:- Benjamin, W. (2015) "Despre conceptul de istorie", in Benjamin, W. Limbaj și istorie. Translated from German by M-M. Anghelescu and G. State. Cluj-Napoca: Tact.

- Flanagan, R. (2025 [2023]) Întrebarea 7. Translated from English by P. Iamandi. Bucharest: Litera.

- Oswald, A. (2013) Memorial. A version of Homer's Iliad. New York: W.W. Northon & Company.